How To Grow A Nation

How To Grow A Nation

Industrial policy can make or break a nation.

Developing countries, due to lack of technical know-how and training, have large amounts of unskilled labor. Factories can absorb this unskilled labor and train workers on the job.

With machines, workers can do more, much more, with less time and effort. This creates material abundance.Of course, we can debate about whether or not technology-led growth is good or bad for society, but that's for another article. Were the Middle Ages were better days? Were the hunter gatherer epoch was the best days? I'm not convinced. And neither are most people. I don't know of any government that wishes to roll-back the industrial revolution. And if you have enemies with modern military technology, it's simply not an option. I'd be happy rolling back to the Garden of Eden, but definitely not the Middle Ages, nor hunter-gatherer days. We over-romanticize what we don't have. Live the hunter-gatherer life for a few months-- most of you will be bored. Thoreau's main pleasure in Walden was not hoeing beans, but living the contemplative intellectual life built for him by millenia of organized human civilization.

And so, the trillion dollar question:

What makes good industrial policy?

If we reject the modern trend to reduce economics to a few, oversimplified, memes and numerical models, the next best thing to do is to study history, finding guidance from past successes or different nations. How did they do it? Where did the others go wrong? What can we take and apply to countries today?

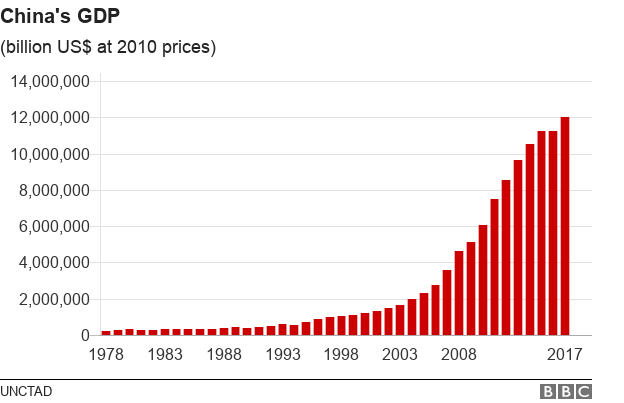

In How Asia Works, Joe Studwell explores a slice economic history of great relevance to all developing nations: the industrialization of East Asia. After World War II, China, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, were all similarly poor. Today, the former three are leagues ahead of the latter. China, Taiwan, and South Korea leaped from agrarian to first-world in just a few decades.

Disciplined Parenting

Why is South Korea so much richer than Malaysia? Studwell gives a confident answer.

And the answer doesn't lie in over-restrictive central planning. Isn't negative attitudes towards markets, business, and capital. Isn't nationalizing every major industry.

Nor does the answer lie in the other extreme-- zero-intervention libertarianism. It's not allowing all foreign competition and investment.A strategy often enforced onto developing countries by the WTO, along with many famous economists, in spite of the fact that it has never worked in history.

The answer lies in the middle: subsidies and protection for key industries, but with a few important qualifications to keep business-leaders honest and aligned with the goals of national development.

Infant Industry Protection

"Infant industry protection" means protecting new domestic industries from global competition. Infant industry protection is a controversial strategy, because "protectionism" is a dirty word in modern economic discourse, governed largely by free trade dogmatists. Any kind of protection is said to create ineffeciencies in the market, and encourage laziness and corruption. It's often associated with fascism and xenophobia.

These criticisms are extremely unfair. Here's a great and fun argument by Ha Joon Chang which highlights, with an analogy to parenting, the necessity of protecting new or infant industries. The article is very entertaining and worth reading in full, but I'll give a quick summary so we can refer to his analogy going forward.

I have a six year old son. He's spoiled and does no work. He just sits around coloring all day. They teach nothing practical at his elementary school. They read about hungry caterpillars. What's the point? How will this make him money? He should get a job. Real life is the best teacher. He's old enough to work at a clothing sweatshop. I'll pull him out of school and put him there. He must learn self-reliance and discipline. He must learn the value of money.

This is clearly deranged. Children need time for education and development, and they must be supported through this time. If my son thirty and still sitting at home, reading childrens books and coloring, then sure, I can be strict and push him to get a job. But I can't expect him to compete when he's six.

It's the same for industry. Different stages of development require different policies. You can't tell new entrepreneurs in a developing country that "Protections create ineffeciencies in the market. And it'll make you lazy. No tariffs, no subsidies, you need to compete with first world countries with hundreds of years of experience. It'll build character. Good luck."

Let's extend the analogy further. You probably want to guide your kid to do something useful for society, and to have a sense of civic responsibility. You don't want to force them to be a doctor or lawyer. That's too oppressive. But you also don't want to say, "you can be anything you want", and then they dedicate their lives to building casinos or marketing cigarettes, profiting from vice and addiction.

It's the same for industry. You don't want to tell your entrepreneurs exactly what they can and can't do. This kind of central planning is doomed to fail. But you should at least guide them away from useless sectors, lest you end up like Malaysia, whose richest businessman, Lim Goh Tong, dedicated his life to building casinos.

You don't want to to spoil your kids, spoiling them will stunt self-reliance, but too little support and their life will be needlessly hard.

It's the same for industry. You want to give your entrepreneurs access to capital so they can grow. And while they learn the ropes, you want to shield them from well established multi-nationals, who will easily out-compete or undercut them. But you don't want to let them to get entitled--collecting subsidy checks without doing any real work, feeling like kings only because all real competition has been pushed out.

This last scenario is the main argument of anti-protectionist economists like Arvind Panagariya against protectionism. Protected industries get lazy. They must be forced to compete or they'll exploit the government for free money.

So how do you find the right balance? Studwell says: export discipline.

Export Discipline

Export discipline is giving large subsidies to critical industries, but ONLY IF they export a percentage of their product. This export requirement sets a minimum bar of global competitiveness.

It's a brilliant solution, because it gives you an objective metric by which to judge your subsidy recipients. Business leaders won't be able to fool you with powerpoints promising the moon-- if only you'd just grant them one more interest free loan.

South Korea also ranked companies in budding industries by this objective metric. To businesses that failed to meet expectations, they cut aid, or forced them to merge with higher performers.

More analogies: let's say your kid tells you he needs a laptop "to help him study". You know that's a lie. He wants that laptop for Netflix. You're fine if your kid goofs off a little bit, you don't want to suck all the fun out of his life, but you must make sure he doesn't waste all his time. So, you tell him you'll buy him a laptop, with one catch: you'll sell the laptop if his grades don't improve (grades are a bad metric, but you get the picture).

With export discipline tied to subsidies, you completely control how much competition your industries should handle. They still have the domestic market all to themselves, but their heads are oriented towards eventually becoming world class. Building a world class product requires R&D investment, and a deep understanding the technology you're working with. It requires foregoing expensive contractors to learn how to do things youself. It requires long term investments in building cheaper, local, capability and training local talent.

These investments have network effects that spread across industries. Knowledge is spread throughout the country, different industries begin to support each other (steel is the kingpin), and a technical curriculum is organically developed and taught on-the-job.

South Korea's Tiger Mom

South Korea is a great example of a country that successfully implemented export discipline-- with a emphasis on the "discipline". Their industrialization was led by president Park Chung Hee.

At the start of Park Chung Hee's tenure, he threw most of South Korea's big business leaders into jail, and intimidated them until they agreed to stop with easy profits and crony capitalism, and only take up projects that would help Korea's industrial infrastructure. He emphasized industries that built infrastructure and engineering know-how, like steel, automobiles, and shipbuilding, as opposed to industries like liquor or real-estate.

He was also strict with capital controls. He wanted Korea to be self-reliant and build their own machines, not blindly push buttons on Japanese equipment they didn't understand. Poor countries make clothes. Rich countries make machines that make clothes. Foreign machines were only imported in order to take apart and learn from. The long-term goal was self-reliance. Technological dependence was to be avoided at all costs. Building your own production equipment is tough at first, but worth it in the long run. It also enables you to build custom equipment, sets you up for higher margin opportunities in selling these machines, and builds the knowledge needed for future innovation.

Hyundai Construction is a great example of this. They started off mixing cement using foreign equipment, but studied this equipment to figure out how it worked. They mastered the machine designs to such a degree, that they then went on to build custom cement plants in other countries, like Saudi Arabia.

Park Chung-Hee kept entrepreneurs from outsourcing the challenging parts of their processes to more advanced countries like Germany, or rely on fancy foreign machines they didn't understand. And, like Deng Xiaoping in China, he also restricted consumption, especially imported consummables, to favor investment. Smoke a foreign cigarette and you were labelled a traitor.

Though Park Chung-Hee was strict on WHAT manufacturers could build, he imposed no limit on the amount of money entrepreneurs could make. The Korean entrepreneurs, though they were bullied a bit, still ended up rich. This was another wise decision. Park knew most of these guys were driven primarily by greed. Instead of trying to shape them into selfless servants, he carefully structured their environment so that their selfishness would benefit the nation. This kind of state-led capitalism-- harnessing the power of free markets and self-interest, but directing it towards sectors that benefit the rest of the society-- seems to do well for developing countries.But I still need to study more rigorous comparisons of communism, Nehru-style socialism, state-led capitalism, and libertarianism in developing countries.

Malaysia's Elephant Dad

Mahathir Mohamad was Malaysia's prime minister from 1981 to 2003. Compared to Park Chung Hee, he was much more laid back. Mahathir knew industry was important, but he didn't force Malaysia's oligarchs to master important industries like steel. Instead, he was coerced by the smooth-talking business elites to dole out licenses for yacht and casino companies. Fifty years later, the casino guys were drowning in money, but there were no foundational improvements in technology or infrastructure to the Malaysian economy. This a great example of "you can be anything you want honey" style parenting going wrong.

Mahathir also gave Malaysian business elites contracts for infrastructure projects, like bridge-building. But unlike Park Chung-Hee, he didn't demand that Malaysians build the bridges themselves.

This is like the spoiled kid paying a classmate to do his homework for him-- Malaysian businessmen accepted the contract but outsourced all the hard work to foreign construction companies, including, South Korea's Hyundai Construction. Then, just like the empty-headed rich kid bringing home an A on his report card, Malaysia's businessmen showed Mahathir these illusions of learning and development.

From the book: "The oligarchs simply showed the premier an efficient power station built by Siemens, or a mobile phone service based on Ericsson technology, or giant towers designed by an American architect and built with north-east Asian steel, and collected the rent for being able to use that imported technology efficiently. Mahathir could be a pain to work for, but ultimately Malaysia’s billionaire elite ran rings around him."

The Relevance Today

Many economists, especially those educated in the US, are blasting India's policies for "sliding back" into protectionism. They argue India tried protectionism in the 1950s - 1980s and it failed them. But it's absolutely absurd to say they failed "because of protectionism". If we remain willfully ignorant of nuance, we can construct any argument we want. Let me roleplay as an economist for a moment: "Mexico went with NAFTA for 23 years and they're still poor. Therefore they failed because of free trade. Therefore free trade is bad. Therefore no country should do free trade."

There is smart protectionism, applied carefully to certain industries in certain points of development, and clumsy protectionism, that encourages corruption and cannot be repealed. Protectionism is a spectrum and the details are important. No major country in the history of the world has succeeded without some form of protectionism.

Most countries still have a lot of catching up to do. Times are different, money is different, cultures are different, but many lessons from East Asian success are still valuable.

Related Reading

Ha-Joon Chang, Bad Samaritans: On the myth of free trade and the necessity of infant industry protection.

Park Chung-Hee, Korea Reborn: Park Chung-Hee's vision for a developed Korea, in his own words.